Japan

Autogas market trends

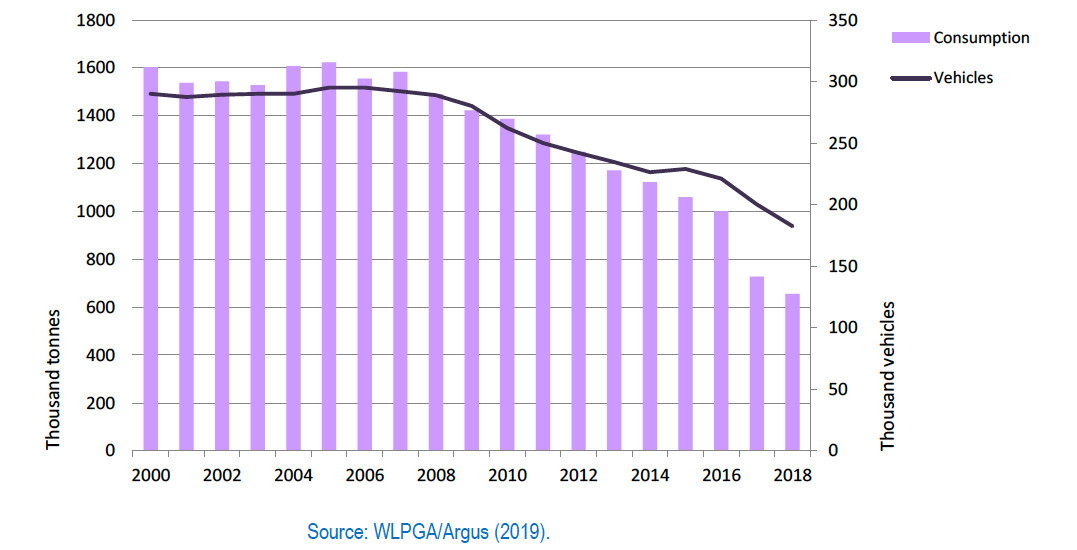

Japan has a long history of Autogas use stretching back to the 1950s, but the market has been in decline for several years. Consumption slumped by more than a quarter to 728 000 tonnes (mostly butane) in 2017 and by a further 10% to 656 000 tonnes in 2018 (Figure B11.1). Autogas now accounts for only about 1% of total road-transport fuel consumption. Autogas consumption was flat at around 1.5-1.6 Mt between 2000 and 2007, but then began to decline steadily, mainly because of a gradual fall in the number of Autogas vehicles and a significant improvement in the fuel economy of the vehicle fleet. Autogas accounts for just 4% of total Japanese LPG consumption. Official projections point to a further drop of around a quarter in Autogas use over the five years to 2024.1

Autogas consumption and vehicle fleet – Japan

The Autogas fleet contracted from a peak of just under 300 000 vehicles in 2006 to 182 000 in 2018 – a mere 0.2% of all motor vehicles in Japan. Taxis, most of which run on Autogas, account for the bulk of the Autogas fleet and commercial fleet LDVs, HDVs and minibuses account for almost all of the rest. A contraction in the overall size of the taxi fleet and the growing penetration of diesel cars are the principal reasons for the decline in the overall number of Autogas vehicles.

Most Autogas taxis are dedicated mono-fuel vehicles. The two largest OEMs are Nissan and Toyota. Both carmakers sell taxi cabs that meet government criteria for the so-called Universal Design Taxi Cab (UDTC), which can accommodate passengers in a wheelchair together with other passengers in the same cabin. In 2016, Toyota introduced a van-type hybrid vehicle fuelled by Autogas, which qualifies as a UDTC.1 More recently, Toyota launched a new hybrid Autogas taxi, the “JPN Taxi” with fuel economy of 19.4 km/litre and correspondingly low CO2 emissions. Since the beginning of 2018, 1 000 units are being sold monthly in Japan.2 There are 1 404 refuelling stations selling Autogas in Japan – more than one-quarter fewer than in the mid-2000s.

Most Autogas taxis are dedicated mono-fuel vehicles. The two largest OEMs are Nissan and Toyota. Both carmakers sell taxi cabs that meet government criteria for the so-called Universal Design Taxi Cab (UDTC), which can accommodate passengers in a wheelchair together with other passengers in the same cabin. In 2016, Toyota introduced a van-type hybrid vehicle fuelled by Autogas, which qualifies as a UDTC.1 More recently, Toyota launched a new hybrid Autogas taxi, the “JPN Taxi” with fuel economy of 19.4 km/litre and correspondingly low CO2 emissions. Since the beginning of 2018, 1 000 units are being sold monthly in Japan.2 There are 1 406 refuelling stations selling Autogas in Japan – more than one-quarter fewer than in the mid-2000s.

Government Autogas incentive policies

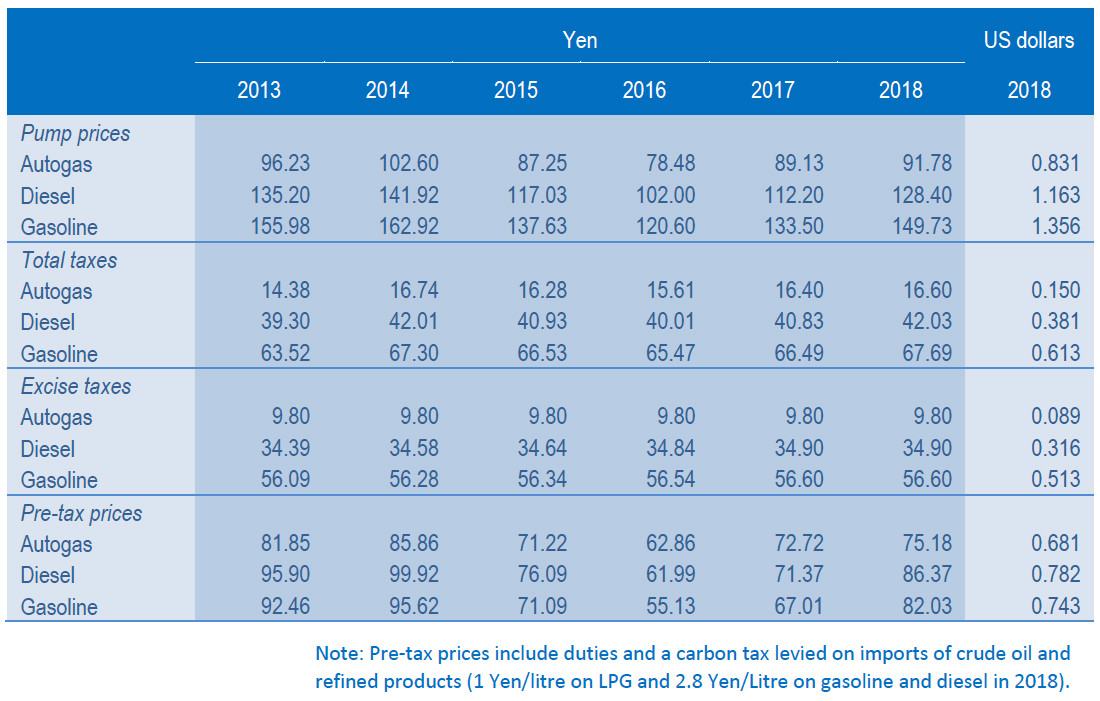

The Japanese government has maintained lower excise duties on Autogas than on diesel and gasoline for many years, though the size of the differentials has generally been large enough to incentivise the use of Autogas only in high-mileage vehicles. The duty on Autogas has not changed for more than a decade; those on gasoline and diesel rose very slightly through to 2017 and have been unchanged since. The duty on Autogas is currently less than one-third the level of that on diesel and less than a fifth of that on gasoline (Table B11.1). In addition, import duties and a carbon tax – both of which are relatively small – are levied on imports at a lower rate on Autogas than on gasoline and diesel (these charges are reflected in pre-tax retail prices).

The pump price of Autogas is currently 71% of that of diesel and 61% of that of gasoline in per-litre terms. Price differentials widened significantly in 2018, boosting the competitiveness of Autogas, as the pre-tax retail price of Autogas rose less in percentage terms than that of both other fuels due to divergent trends in international prices.

A scheme that provided grants for Autogas vehicles ended in March 2017. It covered up to 50% of the additional cost of buying an OEM Autogas vehicle or converting an existing vehicle up to a maximum of 250 000 yen (¥). (around $2 300). A total of ¥91 million ($830 000) was budgeted for the scheme, the same as in 2015. Taxis did not qualify for the grant. To compensate for this change, the government has added Autogas vehicles to the category of “eco-car”, which qualifies for a reduction in the purchase tax for two years from April 2017. In addition, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is offering grants of up to ¥600 000 (roughly $5 500) for UDTCs that use electric or hybrid motors, including Autogas. The Japanese government has also scrapped grants of up to ¥150 000 ($1 360) previously offered to the buyers of those diesel-powered vehicles categorised as “clean”.

Automotive-fuel prices and taxes – Japan (euros/litre)

A scheme that provided grants for Autogas vehicles was ended in March 2017. It covered up to 50% of the additional cost of buying an OEM Autogas vehicle of converting an existing vehicle up to a maximum of 250 000 yen (¥). (around $2 500). A total of ¥91 million ($900 000) was budgeted for the scheme, the same as in 2015. Taxis did not qualify for the grant. To compensate for this change, the government has added Autogas vehicles to the category of “eco-car”, which qualifies for a reduction in the purchase tax for two years from April 2017. In addition, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is offering grants of up to ¥600 000 (roughly $6 000) for UDTCs that use electric or hybrid motors, including Autogas. The Japanese government has also scrapped grants of up to ¥150 000 ($1 500) previously offered to the buyers of those diesel-powered vehicles categorised as “clean”. The government’s new Basic Energy Plan, announced in April 2014, sets an objective of increasing the role of Autogas, though it does not set any targets.

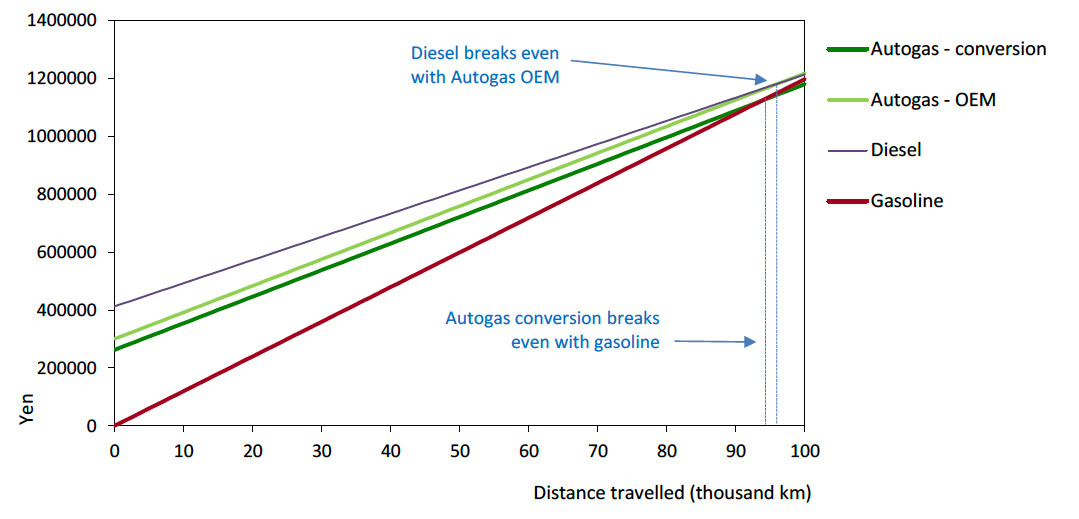

Competitiveness of Autogas against other fuels

Autogas currently struggles to compete against either diesel or gasoline. Autogas is cheaper than diesel, but only up to 96 000 km, while Autogas breaks even with gasoline at 94 000 km in the case of a converted LDV and over 100 000 km for an OEM vehicle (Figure B11.2). This analysis demonstrates clearly why the Autogas market is contracting. Restrictions on the use of diesel by taxis on environmental grounds and the reintroduction of incentives for Autogas will be needed to reverse this trend.

Running costs of a non-commercial LDV, 2018 – Japan