India

Autogas market trends

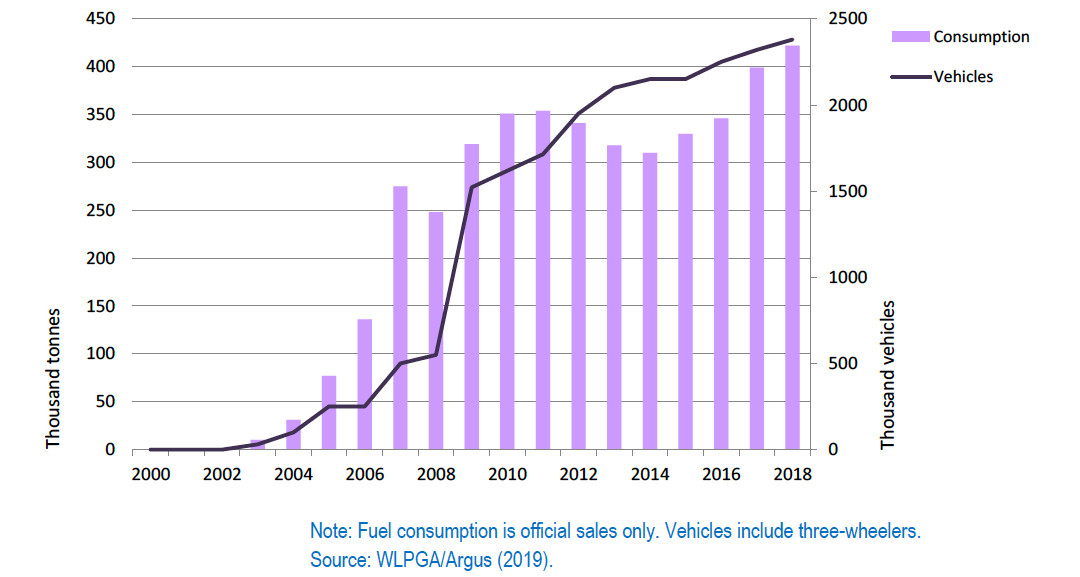

There are now an estimated 2.38 million vehicles capable of running on Autogas in India, the majority of which are three-wheelers (which explains why average consumption per vehicle is only around 300 litres per year). The number of conversions of vehicles to Autogas are running at about 10-15 000 per month.1 Roughly 7% of all the vehicles on the road in India (excluding two-wheelers) run on Autogas. The main vehicle manufacturers now offer factory-fitted Autogas models, such that OEM vehicles now make up about two-thirds of new Autogas vehicle registrations. There are around a dozen OEM Autogas models currently on sale in India, including those made by Bajaj Auto, Maruti Suzuki, Tata Motors, General Motors and Hyundai. Interest among carmakers in marketing more models is growing with the recent fall in Autogas prices relative to gasoline and diesel (see below). In many cities, a large share of three-wheeler rickshaws – an important means of public transport in India – has been converted to run on Autogas.

There are 1 350 filling stations selling Autogas across the country, spread over more than 500 cities (mainly in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu).2 Three state-owned companies – Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum – own around 700 (about 55%) of these stations, with the rest owned by a number of private companies, notably Reliance, Total, SHV, Aegis Logistics and IPPL.

Autogas consumption and vehicle fleet – India

There are now an estimated 2.32 million vehicles capable of running on Autogas in India, the majority of which are three-wheelers (which is one reason why average consumption per vehicle is only around 300 litres per year). The number of conversions of vehicles to Autogas are running at about 10-15 000 per month.1 Roughly 7% of all the vehicles on the road in India (excluding two-wheelers) run on Autogas. The main vehicle manufacturers now offer factory-fitted Autogas models, such that OEM vehicle now make 65% of new Autogas vehicle registrations. There are around a dozen OEM Autogas models currently on sale in India, including those made by Bajaj Auto, Maruti Suzuki, Tata Motors, General Motors and Hyundai. Interest among carmakers in marketing more models is growing with the recent fall in Autogas prices relative to gasoline and diesel (see below). In many cities, a large share of three-wheeler rickshaws – an important means of public transport in India – has been converted to run on Autogas.

There are 1 300 filling stations selling Autogas across the country, spread over more than 500 cities (mainly in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu).2 Three state-owned companies – Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum – own around 700 (about 55%) of these stations, with the rest owned by a number of private companies, notably Reliance, Total, SHV, Aegis Logistics and IPPL.

Government Autogas incentive policies

The main public policy incentive for Autogas in India is an excise tax exemption. The Indian government has deregulated retail prices of Autogas, gasoline and diesel: oil marketing companies are now free to revise their Autogas prices every month in line with international prices, though they have to seek permission from the Ministry of Oil if they want to revise their gasoline prices. Excise duties on gasoline and diesel vary according to the type of fuel: high rates are charged on premium, or “branded”, gasoline and diesel – a practice that has all but wiped out sales of these fuels, even though they provide better engine performances and longevity. Other sales taxes are applied at the national and state levels, including VAT, the rate of which varies according to the fuel and state.

The taxation of LPG changed substantially with the introduction of a goods and services tax (GST) on 1 July 2017, a move that has favoured Autogas. GST is an indirect tax applied across India (except in Jammu and Kashmir) to replace a host of excise and sales taxes levied by the central and state governments. It represents the biggest tax reform in India since the country’s independence. Under this reform, LPG is now taxed at a single rate of 18% across all sectors. The rate has been held down so as not to increase the cost of the fuel to households for cooking too much (previously, taxes on domestic LPG were negligible with most states only levying a small rate of VAT). For the moment, gasoline and diesel are exempted from GST and continue to be subject to state taxes.

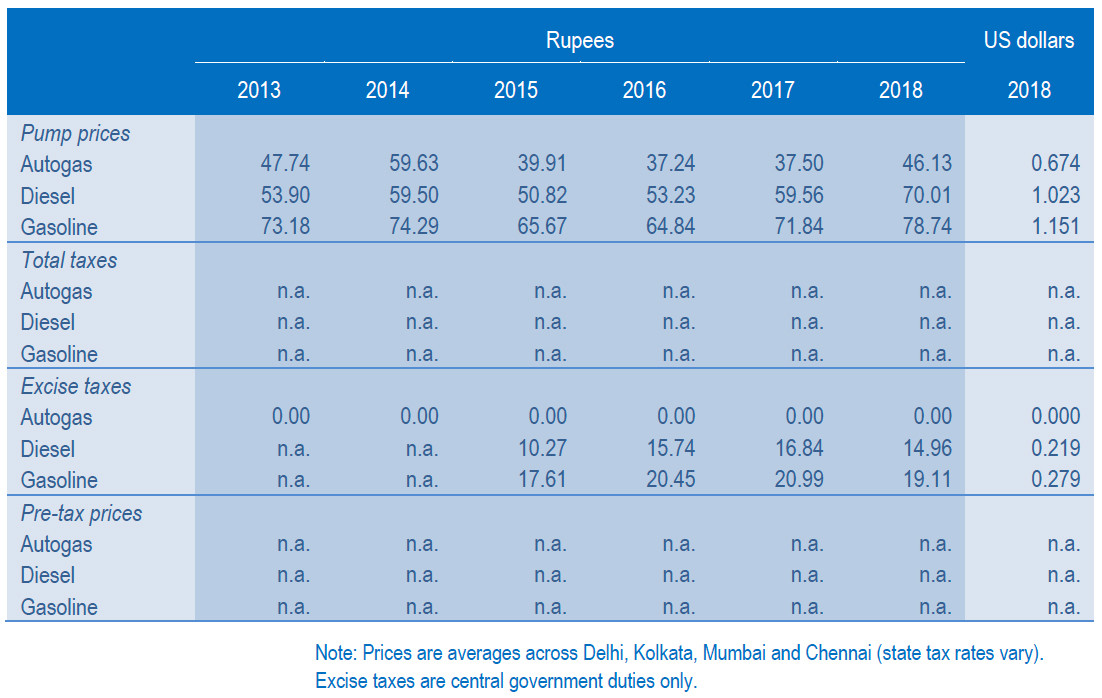

As a result of the tax reform, the average pump price of Autogas rose only slightly in India in 2017, whereas the prices of gasoline and diesel rose significantly, due to both higher taxes and wholesale prices. The prices of all three fuels rose by roughly the same amount in 2018, though the differentials narrowed in percentage terms. The price of Autogas averaged just 59% that of gasoline (up by 6 percentage points on 2016) and 66% that of diesel (up almost 3 points) (Table B9.1). The shift in pricing could provide a significant boost to Autogas demand in India, as well as discouraging the diversion of domestic bottled (cylinder) LPG use to Autogas – a highly dangerous and illegal practice.1

Automotive-fuel prices and taxes – India (euros/litre)

The price of CNG – the other main alternative fuel in India – has generally increased more rapidly than that of Autogas in recent years, undermining its potential as a competitor to Autogas. CNG is not widely available across India. In some cities, including Delhi, rickshaws and commercial vehicles are forced to use the fuel for environmental reasons, just like Autogas.

There are no credits or tax incentives available from the federal government, though several Indian cities, including Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad and Kolkata, make use of fiscal measures to encourage Autogas and other AFVs to address air pollution. Some states, such as Karnataka and West Bengal, on occasion offer grants for converting cars or three-wheeler rickshaws to Autogas. Several Indian cities, including Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad and Kolkata, have introduced measures to encourage or mandate the use of Autogas and other alternative fuels for certain types of vehicle for reasons of local air quality. However, national “type approval” regulations and high rates of GST on conversion kits, which range from 5% to 28%, are reportedly impeding the development of the conversion sector; the Indian Auto LPG Coalition (IAC) is pushing the government to reform these regulations and cut taxes.1

Bangalore has been at the forefront of efforts to promote alternative fuels. It initially focused on three-wheelers, which are now obliged to run on Autogas.

To facilitate switching, the city government offered a subsidy of around 2 000 rupees (around $35) to three-wheeler owners to help cover the cost of conversion. Nearly 75 000 auto rickshaws have already converted to Autogas and about 40 filling stations have been established. Kolkata and Chandigarh have also launched initiative to replace polluting vehicles with Autogas and other AFVs. All public vehicles more than 15 years old had to be scrapped by end-July 2010.2 Many of the 32 000 auto-rickshaws in Kolkata and its suburbs have so far been converted to Autogas. The Union Territory of Chandigarh also allows only Autogas-fuelled three-wheelers to operate on its roads. Chennai and Pune have also encouraged the introduction of Autogas; over 10 000 auto-rickshaws now run on Autogas in Pune. In Delhi and National Capital Region (NCR) region, nearly 10 000 gasoline and diesel cars more than 15 years old were banned from April 2016, unless they converted to Autogas or another clean fuel.3

The central government is increasing its support for EVs, with the budget for the financial year 2017/18 increasing by 42% to 1.75 billion rupees ($26 million).4

The current plan, adopted in 2014, aims to subsidise up to 150 000 cars and 30 000 two-wheelers, with an overall goal of 7 million EVs on the road by 2020. Most subsidies go to hybrids. Some state governments and cities also provide their own subsidies. For example, Delhi, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Lakshadweep, Chandigarh, Madhya Pradesh, Kerala, Gujarat and West Bengal offer a partial or total rebate on VAT. Delhi also provides a 15% subsidy of the list price of certain EVs and exempts such cars from road tax and registration fees.

https://auto-gas.net/mediaroom/indian-lpgindustry-urges-favourable-measures-to-boost-autogas-conversions/

[2] http://www.iac.org.in/auto-lpg-in-india

[3] http://auto-gas.net/mediaroom/nearly-10000-cars-encouraged-to-switch-to-cleanfuels-in-northern-india/

[4] http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/auto/news/passengervehicle/cars/budget-2017-govt-extends-subsidy-for-electric-vehicles-to-fy-18-with42-higherallocation/articleshow/56940069.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium =text&utm_campaign=cppst

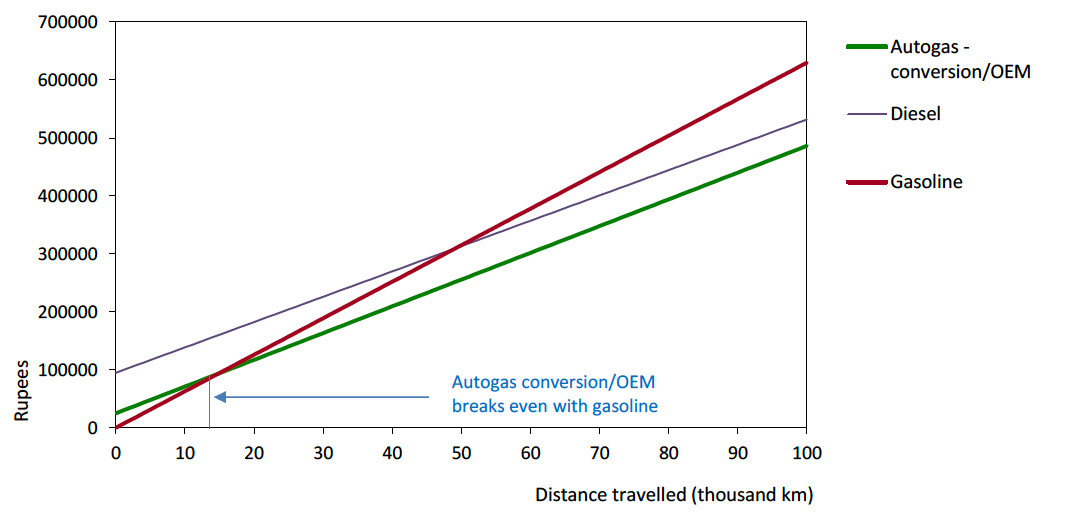

Competitiveness of Autogas against other fuels

Low taxes and, therefore, low pump prices, mean that converting a gasolinepowered vehicle to run on Autogas – or buying an OEM model – both pay back the upfront additional cost on average after just 15 000 km (Figure B9.2). The conversion costs is estimated at 25 000 rupees (about €400) – the same as the cost premium for an OEM car. These costs are very low by international standards because of low labour costs and the type of conversion kits that are installed.

Diesel cars are a lot more expensive – on average, around 95 000 rupees more than a standard gasoline model – such that, although fuel costs per km are still marginally lower for diesel than for Autogas, the latter fuel is always the most financially attractive option. Although CNG prices, adjusted for mileage, are believed to be comparable to Autogas in most cities where the fuel is available, the upfront cost of converting or buying a vehicle is considerably higher than for Autogas.

Running costs of a non-commercial LDV, 2018 – India